In preparation for negotiations for a new contract with Washington, D.C.-area employers Giant Food and Safeway this year, United Food and Commercial Workers Local 400 is liberally borrowing from the “Occupy” activists who made the news last year.

The strategic campaign — including a website it calls “Occupy Giant and Safeway” — is betting that the new brand of activism and its messages will resonate with Giant and Safeway’s shoppers and bring additional pressure to employers to meet the union’s contract goals. To do so, the union is transporting imagery and tactics from Zuccotti Park to zucchini displays. The Local 400 campaign, for example, emphasizes the disparity between pay rates for the employers’ CEOs and for grocery clerks in their respective employ.

“It’s about whether retail will be middle class jobs,” Tom McNutt, Local 400 president, said. “It’s about whether we, the 99%, start getting our fair share of the prosperity that right now flows only to the top 1%.”

Although cautious of the Occupy movement at first, organized labor more recently has picked up on its energy and tactics, resulting in bold strategies like Local 400’s stance at Giant and Safeway. Moreover, some say its populist appeal could be a flashpoint for the labor movement to grow again, arresting a long decline. “The Occupy movement has changed unions,” Stuart Applebaum, the president of New York’s Retail Wholesale and Department Store Union, a division of the UFCW, told the New York Times recently. “You’ll see a lot more unions wanting to be aggressive in their messaging and activity. You’ll see more unions out in the street, wanting to tap into the energy of Occupy Wall Street.”

At the same time, a wave of popular rhetoric from the right is raising defenses against unions in the business community. In particular, business has expressed alarm and indignation over recent changes to union election procedures as well as President Obama’s new appointees to the National Labor Relations Board, with many advocating the NLRB be disbanded. They are also trying to gather support for labor law reform, including measures to make it easier to decertify unions and to outlaw “card check” procedures for union votes.

This movement drew strength from actions over the last year as well, namely the NLRB’s since-withdrawn complaint against Boeing’s 2009 move to manufacture its 787 Dreamliner airplanes in South Carolina rather than in union facilities in its Washington state headquarters.

The Boeing flap relates to South Carolina’s status as a “right-to-work” state that prohibits unions from forcing covered workers to join. Lawmakers in Indiana and Wisconsin spent much of last year grappling over becoming right-to-work states themselves as union officials fretted over the potential of national right-to-work legislation such as that introduced by Sen. Orrin Hatch, R-Utah, last August.

“For too long, American workers have been treated by union leaders as little more than human ATMs,” Hatch said in a speech introducing the Employee Rights Act bill to Congress. “They claim to be progressives, supportive of equality and democracy and the working man. This bill is consistent with those principles, providing working men and woman with a real and meaningful voice in decisions regarding unionization.”

BACKDROP OF RHETORIC

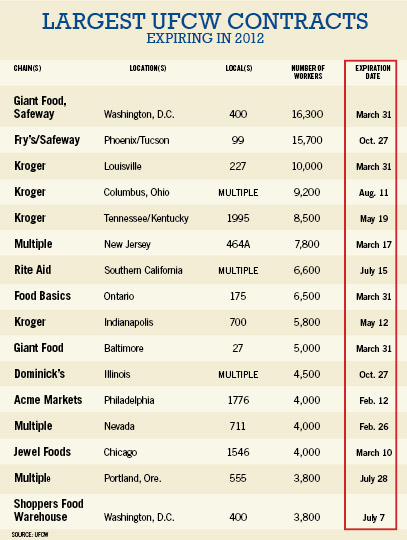

It is against this backdrop of rising rhetoric — and a presidential race likely to feature fierce debate on notions of income inequality and its remedies — that dozens of supermarkets will renegotiate their deals with organized labor unions in 2012. The Giant and Safeway deals with Local 400 — representing more than 16,000 workers and set to expire at the end of March — is the largest such UFCW contract with conventional supermarket chains.

Grand Rapids, Mich.-based supercenter chain Meijer will negotiate with nearly 25,000 employees (that contract has already been settled, a UFCW rep told SN late last week), while workers in Phoenix (Fry’s, Safeway), Indianapolis (Kroger), Louisville (Kroger), Philadelphia (Acme), New Jersey (ShopRite, Stop & Shop, Foodtown) and Portland, Ore. (multiple banners) are also scheduled to negotiate new deals this year.

Tom Becker, chairperson and professor of management at University of Delaware, in an interview with SN said ongoing economic slowness and an unfavorable view of corporations provide the potential for unions to grow again, but noted that management today knows enough to limit the worker dissatisfaction that led to the rise of labor unions in the first place.

“Generally speaking, the [increased rhetoric] is because unions can see there is an opportunity,” Becker said. “One analogy you might use is a sleeping giant. For a long time there hasn’t been an opportunity to make big inroads as a union. Now that the economy’s bad, and perceptions of organizations are unfavorable, the rhetoric is going to crank up because the unions realize they might make some inroads.

“The flip side of that coin is that, as unions have declined over the years, companies moved up the learning curve,” he added. “They realized the reason they have to deal with unions in the first place really boils down to bad management. That’s the No. 1 reason why employees join unions. So by improving management practices and by being more fair to employees, organizations have learned.”

Negative messages over policy, like campaign ads, have gained traction because they are effective, Becker said. “The reason the rhetoric exists in the first place — both in politics and in unions — is that negative ads and aggressive rhetoric really affects people. If it didn’t it would be a useless strategy. Politicians know it does change votes, and if they can make a successful case, even its aggressive and negative, it can change hearts and minds.”

POLITICAL PAYBACK

Others say the level of discourse has risen to score political points — and payback.

For example, the procedural changes passed by the NLRB in December —which could expedite some union elections by reducing litigation and allowing for electronic filings — drew howls of protest from business groups, but will likely have benign influence on the balance of power, said Catherine Fisk, a law professor specializing in labor issues at the University of California-Irvine.

“The only way it can affect organizing is that if you reduce the opportunities to litigate every little thing, you get a decision on an election sooner. But that could be seen to help companies or unions,” Fisk told SN in an interview. “It’s not going to make unions any easier to join, it will just cut down on what the board regarded as excessive delays in elections and update the board’s procedures to make things go faster, such as court proceedings where you can file all the documents electronically.”

Instead, Fisk suggested the NLRB drew fire from groups seeking the same political mileage they gained during the Boeing flap. Mitt Romney, for one, in South Carolina earlier this month aired a campaign ad attacking the NLRB and President Obama over the Boeing dispute, which the agency dropped after the company and its employees reached a new labor deal in December.

“The fact that the NLRB is on the radar screen is probably more attributable to a very organized — and I suspect well-funded — media blitz primarily by employers complaining about what the board had done in particular cases,” she said. “I think that both Republican activists and employers thought that made good politics because it played into an old regional divide in the United States between the non-union and politically conservative South and the more densely union and politically liberal Northeast and Northwest.”

While union representation is down considerably from its peak in the 1950s, Fisk said she believed it was part of a cycle that is likely to rebound at some point.

“If you look back over the last 150 years of American economic history, we’ve seen rises and falls, like economic cycles rise and fall,” she said. “I don’t think there’s any reason to believe that the current decline is a permanent feature of the American economic landscape. I don’t know at what point it will turn around, and what social or economic changes it would take to make workers decide that negotiating collectively is more in their interest than negotiating individually or taking the terms the employers offer. But I don’t think the current decline will last forever.”

A&P’s IMPACT

John Niccolai, president of UFCW Local 464A, Little Falls, N.J., said health care, pension and wages will be on the docket for negotiations with ShopRite, Stop & Shop, Foodtown and King’s when its contract comes up for renewal March 17. The local recently saw its members who work for A&P agree to considerable givebacks, including a wage freeze and reduction in benefits as part of a negotiated settlement to help the retailer out of Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection.

He emphasized that situation wouldn’t affect talks with other employers, saying his goal was to negotiate better deals for his workers.

“I see a greater dichotomy between the interests of management and the interests of workers, and I see that primarily because, overall there’s been a diminution of the union movement in this country,” Niccolai told SN. “I tie the union movement to the growth and preservation of the middle class. As we lose union workers, we lose middle class people. Once people begin to realize that we need to have a strong union movement in order to have a strong middle class you’ll start to see resurgence. And I think that’s happening now.”